LAB 10

Today’s lab will focus on random numbers, indefinite loops, and finding errors.

Software tools needed: web browser and Python IDLE programming environment with the pandas, numpy, and folium package installed.

In-class Quiz

During lab, there is a quiz. The password to access the quiz will be given during lab. To complete the quiz, log on to Blackboard (see Lab 1 for details on using Blackboard).

Random Range

Python has a built-in library for generating random numbers. To use it, you include at the top of your file:

import random

The random library includes a function that’s similar to range, called randrange. As with range, you can specify the starting, stopping, and step values, and the function randrange chooses a number at random in that range. Some examples:

random.randrange(5) returns one of 0,1,2,3,4random.randrange(1,10,2) returns one of 1,3,5,7,9random.randrange(360) returns one of 0,1,2,...,359

Let’s use that last example to have our turtle make a random walk:

Notice that our turtle turns a degrees, where a is chosen at random between 0 and 359 degrees. What if your turtle was in a city and had to stay on a grid of streets (and not ramble through buildings)? How can you change the randrange() to choose only from the numbers: 0,90,180,270 (submit your answer as Problem #10).

Indefinite Loops

We have been using for-loops to repeat tasks a fixed number of times (often called a definite loop). There is another type of loop that repeats while a condition holds (called a indefinite loop). The most common is a while-loop.

while condition:

command1

command2

...

commandN

While the condition is true, the block of commands nested under the while statement are repeated.

For example, let’s have a turtles continue their random walk as long as their x and y values are within 50 of the starting point (to keep them from wandering off the screen):

Indefinite loops are useful for simulations (like our simple random walk above) and checking input. For example, the following code fragment:

age = int(input('Please enter age: '))

while age < 0:

print('Entered a negative number.')

age = int(input('Please enter age: '))

print('You entered your age as:', age)

will ask the user for their age, and continue asking until the number they entered is non-negative (example in pythonTutor).

Finding Errors

Finding, and fixing errors, in your programs is a very useful skill. Let’s look at a program with lots of errors and work through how to identify the issues and fix them. If you cloned the repo above, you will have a copy of errors.py on your computer. When loaded into IDLE, it does not run:

# errors.py is based on dateconvert2.py from Chapter 5 of the Zelle textbook

# Converts day month and year numbers into two date formats

def main()

# get the day month and year

day, month year = eval(input("Please enter day, month, and year numbers: ")

date1 = str(month)"/"+str(day)+"/"+str(year)

months = ["January", "February", "March", "April",

"May", "June", "July", "August",

"September", "October", "November", "December"]

monthStr = months[-1]

date2 = monthStr+" " + str(day) + ", + str(year)

print("The date is" date1, "or", date2+".")

main()

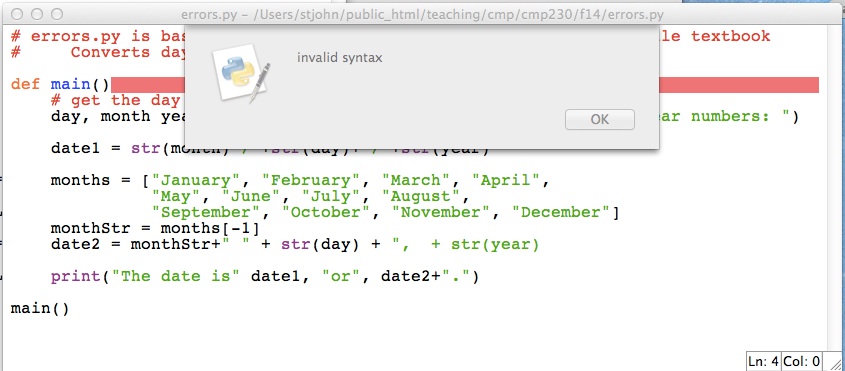

Instead, a dialog box pops up and says “invalid syntax”:

The red line indicates where the intepreter has found an error. Can you tell what it is? Syntax is another word for grammar, so, it most likely missing punctuation or a misspelling of some sort. We have spelled def correctly and have the right number of parenthesis, so, what else is missing?

The answer is after the parenthesis on a function definition, a colon is required. Add that in:

def main():

and try to run the program again.

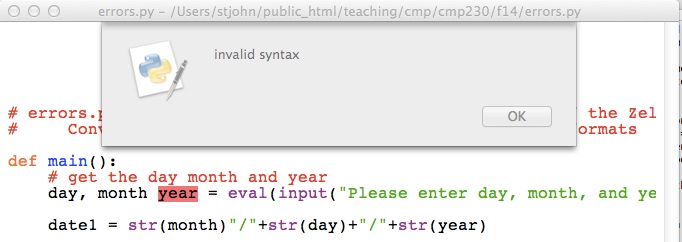

Again, we get a dialog box:

Instead of the whole line being highlighted, only the word year is. The Python intepreter was not expecting year and says there is a grammatical mistake. Since year does not include any grammatical constructs, we need to look before the message to see where the error is. Do you see it?

The answer is lists of variables need commas in between them to distinguish one from the next. Add the comma in:

day, month, year = ...

and try to run the program again.

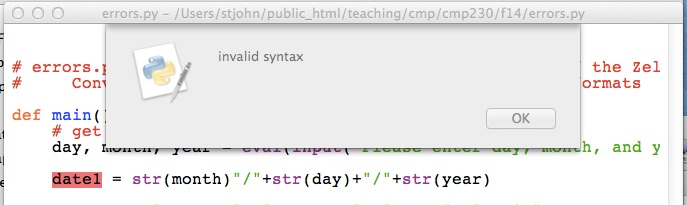

Once more we get a dialog box:

It has highlighted the first item, date1 on the line. That is a name and looks fine. So, as above, let’s look before the highlighted error to see if there’s a problem. The line above it is:

day, month, year = eval(input("Please enter day, month, and year numbers: ")

It did not highlight this line, so, the problem must be at the end. Do you see it?

The answer is we are missing a closing parenthesis. The line has two left parenthesis but only one right parenthesis. Add the right parenthesis in:

... and year numbers: "))

and try to run the program again.

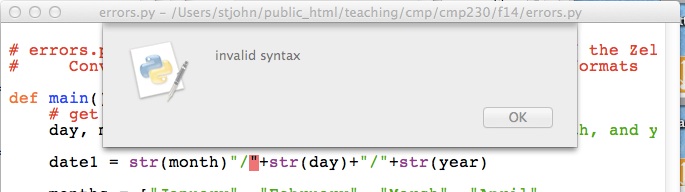

Again, we get a dialog box:

The intepreter does not understand the second “ on the line. Why? What is this line doing? It’s constructing a string and storing it in the variable date1. How do you build a string out of smaller strings?

The answer is to put smaller strings together (called concatenation) we need to use the plus sign (+). The line is missing a plus sign right before the quotes. Add the plus sign in:

date1 = str(month) + "/" ...

and try to run the program again.

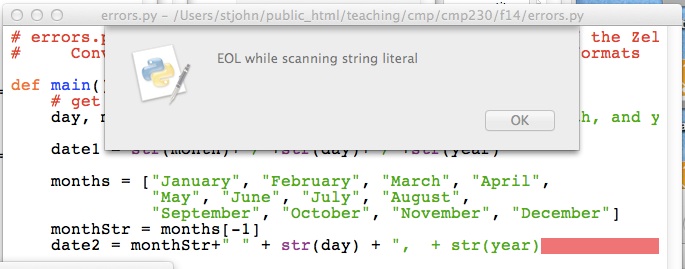

Again, we get a dialog box, but this one has a different message:

EOL means “End of the line”, so, the message says that the end of the line was reached before you finished defining the string. How can you fix this?

The answer is to end the string, using quotation marks. The line is missing a quotation mark at the very end. Add the quotation mark :

...+ ", + str(year)"

and try to run the program again.

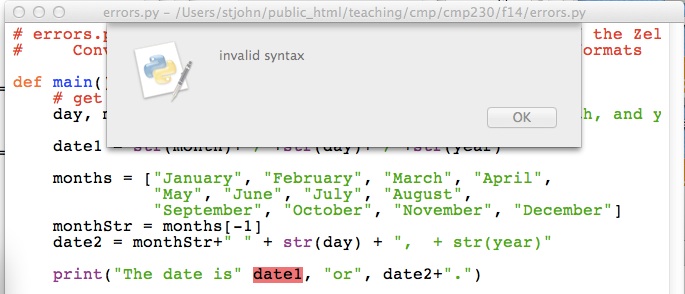

Our familiar dialog box returns:

We have seen this type of error before. How do you fix it?

The answer is lists of arguments need commas in between them to distinguish one from the next. Add the comma in:

... date is", date1 ...

and try to run the program again.

It runs! Now let’s make sure it works. Type in at the prompt:

Please enter day, month, and year numbers: 31, 12, 2014

Uh oh, instead of output, we get the following messages:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/gmaryash/Desktop/errors.py", line 18, in main()

File "/Users/gmaryash/Desktop/errors.py", line 13, in main

monthStr = months\[month+1\]

IndexError: list index out of range

When you see messages like this, go to the very last line:

IndexError: list index out of range

It says that the index for our list is out of range. An index is the item of the list that we’re accessing. For example, months[1] has index 1 and will give us February. The range of the index for a list is 0 to one less than the length of the list. In the case of months, the range is [0,1,2,…,11]. What went wrong when we entered 12 for our month?

The answer is we used month+1 = 12 + 1 = 13 as the index:

monthStr = months[month+1]

which is out of range. What do we want instead? Instead of adding 1, we should subtract 1. Change it in the program:

monthStr = months[month-1]

and try to run the program again.

It still runs, but does it work? Let’s try the same input again:

Please enter day, month, and year numbers: 31, 12, 2014

The date is 12/31/14 or December 31, + str(year).

Something odd is happening at the end – str(year) does not look right. Let’s look at the print statement:

date2 = monthStr+" " + str(day) + ", + str(year)"

The intepreter is treating , \+ str(year) as a string (instead of evaluating str(year)), so, we must have put the quotation mark in the wrong place before. Let’s move it:

date2 = monthStr+" " + str(day) + "," + str(year)

and try to run the program again.

Success! But try a few other inputs, just to make sure. It is always good to try cases that are near the ‘boundary’ of what’s allowed, since those are the places we are most likely to make mistakes:

Please enter day, month, and year numbers: 1,1,2015

The date is 1/1/2015 or January 1,2015.

Please enter day, month, and year numbers: 1, 2, 2003

The date is 2/1/03 or February 1,2003.

Please enter day, month, and year numbers: 4, 7, 1976

The date is 7/4/1976 or July 4,1976.

We have removed all the errors, and the program now runs correctly!

More on Command Line Scripts

In Lab 6, we wrote a simple script that prints: Hello, World. We can write scripts that take the shell commands we have learned and store them in a file to be used later. In Lab 3, we introduced the shell, or command line, commands to create new directories (folders) and how to list the contents of those folders (and expanded on this with relative paths in Lab 4 and absolute paths in Lab 5).

It’s a bit archaic, but we can create the file with the vi editor. It dates back to the early days of the Unix operating system. It has the advantage that it’s integrated into the Unix operating system and guaranteed to be there. It is worth trying at least once (so if you’re in a bind and need to edit Unix files remotely, you can), but if you hate it (which is likely), use the graphical gEdit (you can find it via the search icon on the left hand menu bar).

Let’s create a simple shell script with vi:

- Open a terminal window.

- Type in the terminal window: vi setupProject

- To add text to the file, begin by typing i (the letter i) which stands for “insert”

-

Type the lines:

#Your name here #October 2017 #Shell script: creates directories for project mkdir projectFiles cd projectFiles mkdir source mkdir data mkdir results - Click on the ESC (escape key– usually on the upper row of keys) which escapes from insert mode.

- Type:

:wqwhich stands for “write my file” and “quit” (the “:” is necessary– it tells vi that you want to use the menu commands). - This brings us back to the terminal window. Type ls to see a listing of the directory, which should include the file,

setupProject, you just created. -

Next, we’ll change the permissions on the file, so that we can run it directly, by just typing its name:

chmod +x setupProject(changes the “mode” to be executable).

-

To run your shell script, you can now type its name at the terminal:

./setupProject - Check to see that your script works, type ls to see the new directories your script you created.

Troubles with vi? It’s not intuitive– here’s more on vi:

If you hate vi, just edit using gEdit (the Linux version of TextEdit) or IDLE.

More on Unix: Using Pipes

In Lab 6, we introduced making short programs, or scripts, of Unix commands. In this lab, we introduce a very useful construct to let you glue together simple commands to perform more complex actions.

The command | is called a pipe since it takes the data flowing out of a command and directs it to flow into the next command, much like a pipe directing the flow of water.

For example, if you type:

ls -l

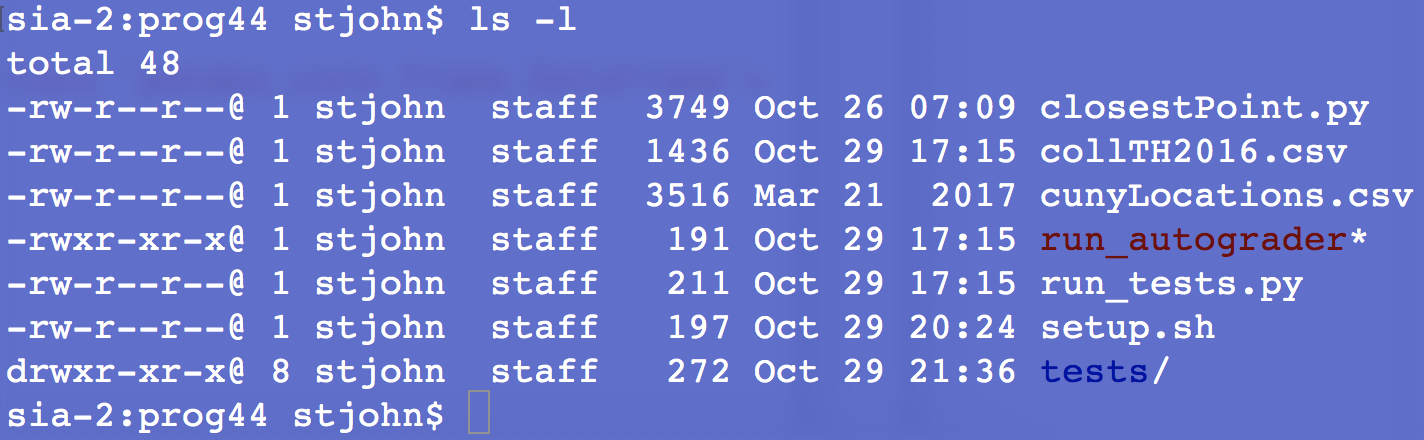

at the prompt, you will see the ‘long’ listing for every file in your current directory. (Note that it’s the letter “L”, not the number “1” that it looks like on some browsers). For example, if I ran this command in my directory for Program 20, I get:

showing 7 files, 6 of which were created in October. Names with ‘/’ after them are directories or folders. ‘*’ indicates files that can be executed (see Lab 6 for how to change the permissions of a file).

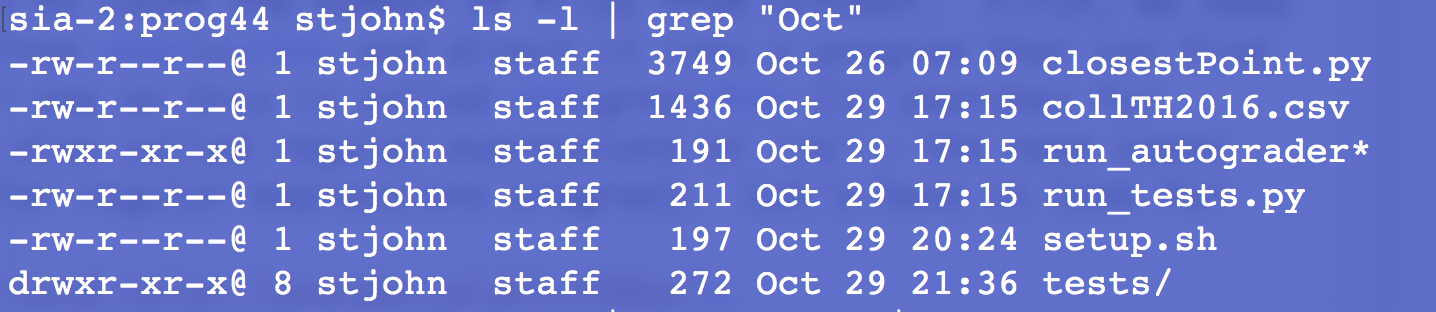

Let’s use a pipe to count the number of files from October. First, we need to take the output from ls and direct it into a program that can find patterns. A popular one on Unix is called grep (it searches for patterns, which are also called regular expressions or ‘re’– the name comes from global search for regular expressions program). Let’s have it look for ‘Oct’:

ls -l | grep "Oct"

Note that between the ls -l and the grep “Oct” is a pipe (|) that directs the outflow from the ls command to the inflow of the grep command:

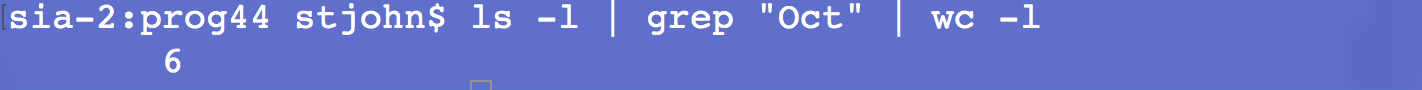

We can use the pipe to take the output of the grep command and send it to a program that counts the number of lines. This program, wc, counts characters, words, and lines. We’ll use the -l option to count lines:

ls -l | grep "Oct" | wc -l

which gives:

the number of files in the directory that were last modified.

How could you make a script that counted the number of .py files in the directory?

When you have the answer, put the single line into a script. Remember to use Unix end-of-lines, since gradescope will run what you submit as a Unix script and will be very confused if you have non-Unix (i.e. Windows-style) end-of-lines. See Programming Problem List.

More Useful Unix Commands

Now that we are creating executable programs, it’s often useful to figure out what kind of file is in your directory. For example, if you were not sure what type of file, hello is, you could type at the command line:

file hello

file is the name of the command, and hello is the input parameter to the command. If you would like to find out the type of several files, you could type each separately:

file hello hello.cpp hello.py

(assuming all of those files are your working directory).

Or, you could use a “wildcard” that matches all files whose names match a pattern. For example:

file hello*

will tell you all type of every file that begins with the hello followed by 0 or more other characters.

Similarly,

file *

will tell you all type of every file in your current working directory.

It’s often useful to figure out which version of a program you’re using (since there could be multiple copies on your computer. To do that, there’s a command, which that will tell which version of the program it’s using by default. For example,

which g++

will show the location of the g++ program.

And Even More Useful Unix Commands!

Here are a few more commands, especially useful when you’re using a public machine, and trying to figure out where things are and what is installed:

-

which: Will tell which version of the program it’s using by default. For example,

which g++will show the location of the g++ program.

-

man: This gives the built-in help pages for the current system. It can be quite useful if you don’t remember all the options for a Unix command. For example,

man sortwill print out information about the command line sort.

- w: This command was designed for multi-user machines and tells you who is logged in and what they are doing. While you are the only one on your laptop, this command is still useful in that summarizes all the activity on the machine in a short table as well as how long the system has been running (‘uptime’). So, if the machine seems sluggish or you’re wondering how much else is going on, it will give a concise summary.

-

more: Allow you to look at output or a file, one screenful at a time. This is incredibly useful when you are trying to read information that scrolls off the screen. Here’s a sample of looking at all programs (from

/usr/bin\-\-a common place to keep them) :ls /usr/bin | moreSay we’re trying to figure out what GNU C/C++ compilers are on the machine, and as a start want to see all the possible programs that contain “cc” (anywhere in their name):

ls /usr/bin | grep cc | sort | moreWe don’t see g++ in the list, so, let’s also look for all that start with g:

ls /usr/bin | grep ^g | sort | moreThe

grep ^gasks for all names that start with “g”.When done, see the Programming Problem List.